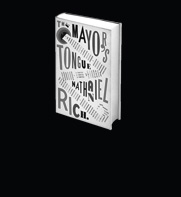

Nathaniel Rich has written two novels:

The Mayor's Tongue (Riverhead, 2008) and the forthcoming Odds Against Tomorrow, which will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April 2013. He is also the author of a book on film noir, San Francisco

Noir (The Little Bookroom, 2005). He lives in New Orleans.

CONTACT:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux (publicity & rights inquiries): fsg dot publicity at fsgbooks dot

com

Nathaniel

Rich (everything else): nathaniel at nathanielrich dot com

Twitter: @nathanielrich

Q&A WITH NATHANIEL RICH ABOUT THE MAYOR'S TONGUE

Q: You kept the existence of

The Mayor’s Tongue secret during the five years you were

writing it. Why?

For a long time I thought it would be presumptuous

to announce that I was working on a novel. At no point was

I certain that all my notes and jottings would add up to a

finished novel, and there were times when I seriously doubted

the sanity, let alone the merits, of what I was writing. I

later found out that my suspicions were well-founded—when

I went back through the early drafts I realize that there were

more than a few ridiculous scenes and subplots, which

I ended up cutting before I showed the book to anyone. In the

end, though, I decided I was ready to take the next step, so

I gave the manuscript to a few friends. But only my nicest

friends.

Q: What led you to write it?

I had a lot of unformed ideas—about language, about

the way people relate to each other—that I wanted to

put on paper. The themes, the characters, and the general conceit

came first, the story later. In the first year or two I wrote

very little, but made notes about the characters and their

relationships. My thought—like my speech—is incoherent

to an embarrassing extent, and I can only make sense of what

I’m feeling or thinking about when I write it down. The

other thing—and I realize this is something of a cliché—was

that I wanted to write a story that I myself would enjoy reading.

Q: You’ve said that this book is extremely personal

but not autobiographical. How so?

Well, none of the events depicted in the book are real, except

perhaps for moments in which a male character humiliates himself

by being inarticulate in front of a girl. None of the characters

are stand-ins for me, and none of them—with the exception

of one or two very minor characters—are based on any

people I know in real life. But the book’s emotions are

very real to me, the themes and ideas are ones that I have

thought about obsessively, and the spirit and the tone of the

writing feels a reflection of my own sensibility.

I felt like I funneled all of my own personal thoughts into

some crazy contraption and, sausage-machine-style, out came The

Mayor’s Tongue.

Q: The failure of language is a central preoccupation

of your novel. How do you develop that theme?

The main characters all want urgently to communicate their

thoughts and emotions, but for different reasons, are unable

to do so. They develop all kinds of strategies, some of them

preposterous, but whether or not they succeed is open to interpretation.

I think this is something we all struggle with; at least I

do.

Q: There are two main stories that flow side by side

in your novel, but never actually intersect. Why did you

use this structure?

I had hoped that the two stories would generate some (perhaps

unconventional) suspense as they unfold, that the reader wouldn’t

be able to help but wonder what the two stories were going

to do. Even if that suspense is spoiled (by an interviewer’s

leading question, for instance), the fact is the characters

in both stories are faced with similar problems but they approach

them from their own perspectives, and reach different conclusions.

My hope is that the two stories reflect and echo each other

in different ways, and I felt that if they were to intersect,

it would cheapen that dialogue. I suppose there would be some

mild pleasure were Mr. Schmitz and Eugene to meet at the top

of a mountain in the Carso and hang out, but that would feel

to me a bit contrived and unnecessary. I think that, by the

end, the stories feel resolved in a way that is true to the

spirit of the novel.

Q: Your novel blends elements from many genres, including

fantasy, realism, mystery, fable, melodrama, and romance,

for starters. How do you describe the result?

I never thought in terms of genre, maybe because I don’t

have much experience in reading genre fiction, except for horror.

I worked hard to make the characters human, vivid, and honest.

It was important to me that the story move along at a steady

pace (this required a good amount of cutting and condensing

over the course of the writing process). I knew I wanted to

explore certain themes, so I concentrated on making those as

nuanced and involved as I could. I also knew from the very

beginning of the project that there would be some slightly

fantastical elements, but I wanted to work up to them gradually,

so that the reader was never jarred by some sudden plunge into

the surreal. I was thinking of a frog in slowly boiling water.

Q: You chose one of Italy’s least-known regions,

the Carso, as the setting for most of your book. Why?

The most prosaic reason is that I was living in Trieste the

summer I started writing the book. That summer, Trieste hosted

the annual international Esperanto festival, so everyone was

walking around speaking this invented language. And this in

a city where people speak a smattering of different tongues—Italian,

German, Slovenian, and Hungarian primarily, but also Triestino,

a thick dialect incomprehensible to other Italians. When you

go up into the Carso, this odd web of languages and cultures

becomes even more pronounced. On the winding mountain roads

it’s often difficult to tell what country you’re

in. The signs are all in different languages.

For a book whose central themes deal with the confusions brought

about by language, the Esperanto sealed the deal. But I also

loved the idea of this isolated land that nevertheless is located

within the borders of one of the most visited and familiar

countries in the world. The region is completely forgotten

by time, and even by its own country—I remember reading

a survey in which the majority of Italians thought that Trieste

wasn’t even part of Italy. It was only annexed in 1954,

and over history it has had numerous national and cultural

identities, having been under the rule of the Romans, Byzantines,

Slavs, the Austria-Hungarians; for several years after armistice

it was even an independent territory. It is the gateway to

the East, the easternmost city in Western Europe—but

it also could be considered the westernmost city in the East.

As Jan Morris wrote, it’s “nowhere.”

Q: Who are some of the writers who have influenced

your work?

I wonder whether there are any writers I love whom I haven’t

tried to steal from. Some of the writers whose work I repeatedly

consulted during the writing of the book were: Flann O’Brien,

Mikhail Bulgakov, Charles Dickens, Italo Svevo, Stephen King,

Kazuo Ishiguro, Katherine Dunn, and Arrian’s history

of Alexander the Great. Jan Morris’s excellent Trieste

and the Meaning of Nowhere was an important resource,

for her depiction of the city and its peculiar hazy identity.

Q: Are you working on another book? Can you say

anything about it?

The new novel has the working title of “Odds Against Tomorrow.”

|